World Landscape Architecture Month

April 30th, 2025

From Contaminated to Community-Ready: How Remediation Opens the Door to Landscape Reuse

In honor of World Landscape Architecture Month, Loureiro highlights the often-invisible foundation of transformative landscapes: environmental remediation. In the post-industrial Northeast, where contamination is more norm than exception, cleanup isn’t a hurdle—it’s part of the design process. This blog explores how Loureiro’s integrated approach turns formerly contaminated sites into vibrant community assets, using a Rhode Island Superfund project as a case study. From engineered caps to native meadow design, discover how technical remediation and thoughtful landscape architecture come together to create spaces that are not only safe, but meaningful, resilient, and ready for community use.

When we think about landscape architecture, we often focus on the finished product: paths winding through a restored wetland, native grasses swaying in the breeze, a community reconnected to a river it once overlooked. But the truth is, many of these projects don’t begin with design—they begin with remediation.

This World Landscape Architecture Month, Loureiro is celebrating not just the landscapes we see, but the invisible work that makes them possible. Because in the post-industrial Northeast, where so many of our sites come with a complex past, site contamination isn’t a constraint—it’s a design condition. Transforming a fenced-off liability into a shared community asset takes more than good intentions. It takes technical precision, regulatory fluency, and a clear vision for what comes next.

Remediation is the Foundation, Not a Phase

At Loureiro, we believe that environmental remediation and landscape architecture aren’t mutually exclusive disciplines; they’re two parts of the same process. Nowhere is that more evident than at a Superfund Site in Rhode Island, where Loureiro helped to restore a contaminated riverfront site for two residential apartments.

The project site carried a layered industrial history. It was once home to a textile mill, then a chemical manufacturing operation, and finally a drum reconditioning facility. Decades of unchecked activity left behind a complex mix of contaminants, including dioxins, PCBs, heavy metals, and solvents. These pollutants had migrated beyond the original operations footprint, impacting not only surface soils but also floodplain areas, wetlands, and river sediments. By the time the site was designated a Superfund Site in the 1990s, a residential complex had already been built, and three areas of significant contamination were fenced off, isolating portions of the community from their own backyard. From the start, Loureiro understood that containment wasn’t enough—the remediation had to support a long-term vision for restoring safe, meaningful use of the land.

“The cap design determined everything,” said Dave Payne, Project Manager. “Drainage, grading, access—it all had to be engineered first. Only then could we talk about what the space could become.”

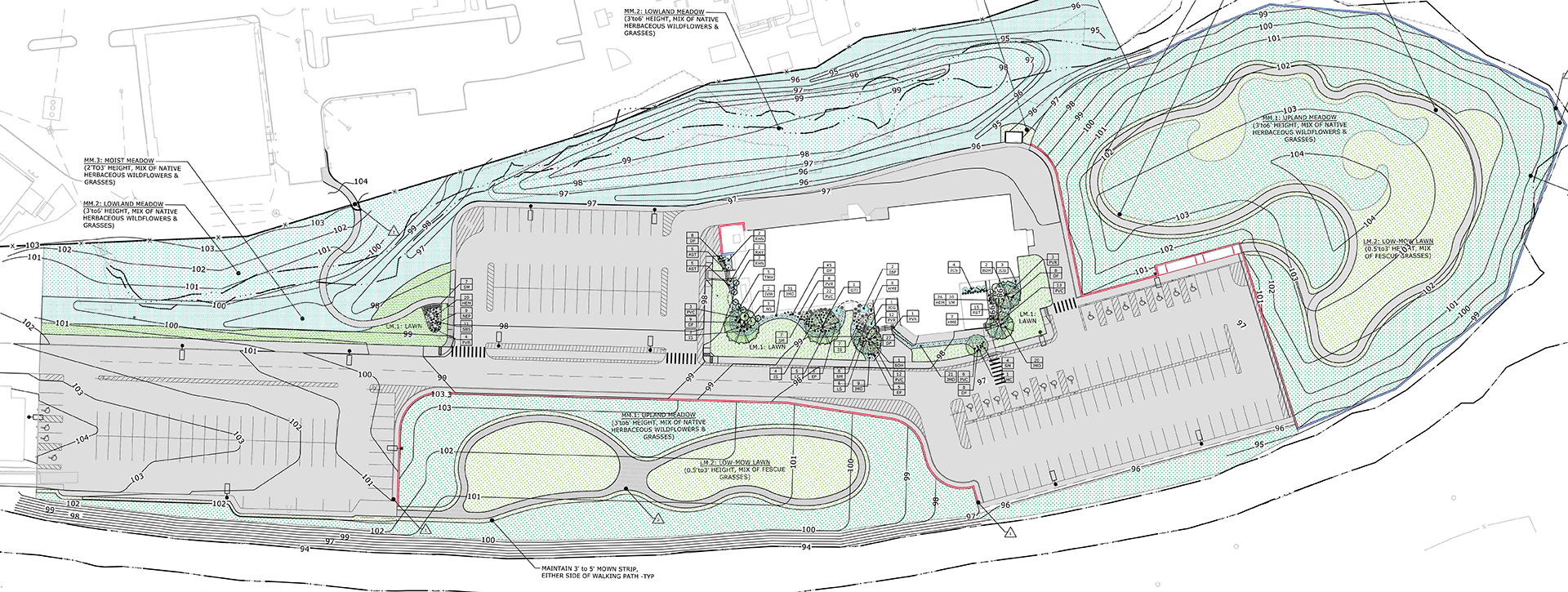

Loureiro designed and implemented a multi-layer cap system that met strict EPA criteria for long-term protectiveness while supporting future site use. Contaminated soils were consolidated on-site and covered with a carefully engineered cap: an impermeable barrier topped with protective soil layers, finished with six inches of topsoil to support vegetation. Because the site is bordered by development and the waterfront on all sides, cap elevation and drainage design were tightly constrained requiring creative grading and the extension of existing municipal stormwater infrastructure. The resulting topography informed every downstream decision: where walking paths could be placed, which plant communities would thrive, and how to manage runoff without compromising cap integrity. Stone dust paths, shallow-rooted pollinator species, and low-mow meadows were all selected not just for appearance, but for technical compatibility with the remediation system.

Designing for Durability and Access

When you’re working on remediated land, every design decision is technical. Walking paths aren’t just aesthetic—they’re drainage infrastructure. Meadow species aren’t just native—they’re low-maintenance, shallow-rooted, and flood-tolerant. Retaining walls don’t just shape space—they protect the engineered cap from erosion and future excavation.

That’s the kind of coordination Loureiro brings to complex sites: a practical, systems-level understanding of how cleanup and landscape can work together.

“As engineers, we’re trained to focus on function,” Dave added. “But partnering with landscape architects reminded us that form matters too—especially when you’re trying to rebuild trust in a place that’s been behind a fence for years.”

Community Perspectives and the Long View

As noted in the EPA’s 2024 Five-Year Review, the remedy at the Superfund Site is functioning as intended. But community responses have been mixed. Some residents expressed concern about tree removal and the unfamiliar look of naturalized landscapes. Others welcomed the new walking paths and open space but voiced concerns about maintenance and flooding.

Loureiro understands that transformation takes time—not just ecologically, but socially. That’s why we don’t treat remediation as a handoff. We stay engaged through post-construction inspections, operations and maintenance support, and ongoing collaboration with stakeholders.

More Than Cleanup: Preparation for What’s Next

Whether it’s a brownfield near a future school site, a closed landfill on the edge of a trail network, or a flood-prone site waiting to be reimagined, Loureiro approaches every remediation project with an eye toward what’s next. We don’t just clean up land. We prepare it—for people, for ecosystems, and for design.

So this month, as we celebrate landscape architects and the spaces they shape, we also celebrate the groundwork that makes it all possible.

Because remediation isn't a side story — it's the starting point for many resilient landscapes.